By Wynn McDonald, Staff Writer

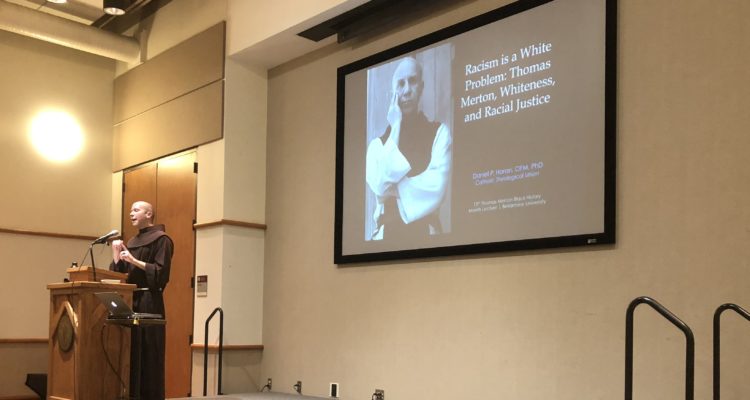

Last Thursday, I had the pleasure of attending a long-standing tradition at Bellarmine: the thirteenth annual Thomas Merton Black History Month Lecture featuring Father Daniel Horan, OFM.

For over 10 years, the Thomas Merton Center has brought speakers to campus to reflect on the theology and civil rights dialogues of Bellarmine’s favorite Trappist monk. Past keynoters have included Dr. Vincent Harding, Dorothy Cotton and Bishop Edward Braxton.

The much-anticipated lecture was open to the public, and Hilary’s was packed 10 minutes before its start. Bellarmine students, faculty and Merton enthusiasts from far and wide crowded together to hear Horan speak on the topic “Racism is a White Problem: Thomas Merton, Whiteness, and Racial Justice.”

With all this fanfare—standing on the campus chosen by Merton himself as the repository of his revered manuscripts, and the relationship with whom he once called “a continued honor and joy”—Horan appeared perfectly at ease.

“Thank you to all of you for joining me this evening,” Horan said, opening the lecture with a smile and an even, grounded tone. “Can you hear me okay?”

At just 35 years old, Horan could not be more at home in a setting like this.

An ordained Franciscan Friar of the Holy Name Province in New York, Horan has given lectures on Merton and Franciscan theology all around the U.S., Canada and Europe. He earned a doctorate in systematic theology from Boston College, and has already written 12 books on spirituality, including the award-winning volume “The Franciscan Heart of Thomas Merton: A New Look at the Spiritual Influence on his Life, Thought, and Writing” (2014). Among other engagements, he currently serves as an assistant professor of systematic theology and spirituality at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago.

On this particular occasion, he was tasked with channeling and interpreting the famous monk’s thoughts on the reality of the black experience in America. His focus was the role of white racial identity in relation to social justice.

The structure of Horan’s lecture was simple. Over the course of an hour, he touched on three primary subjects: “whiteness” and the reality of structural racism, the prophetic nature of Merton’s anti-racist writings, and the limits of Merton’s own white self-criticality.

However, after a brief introduction, he made one important point clear.

“Given that there are a number of people in this room that look like me,” Horan said, “I will acknowledge first and foremost that some of what I’m going to say is going to be uncomfortable—and that’s okay. Be uncomfortable, and sit in it.”

This touched the heart of Horan’s message, and by extension, Merton’s. In a society that systematically holds the needs, accomplishments and problems of one race above another, no one can hide from the ugly reality: if you benefit from this system, you are complicit. To fight for social justice, you must first be fully conscious of this fact—no matter how uncomfortable it may feel.

Merton, like Horan, was aware of the privileges granted him by his race, and spent much of his life identifying and decrying the immensely problematic racial structure in America. More notable still, this enlightenment came during what was perhaps the most socially tumultuous time in the country’s history.

In the mid-1950s and ‘60s, while civil rights rallies and violent racial backlash rose up all around him, Merton “turned to the world” with a conviction and moral clarity that was unprecedented among white Catholic clergy at the time, according to Horan. His outspoken criticism even resulted in a correspondence with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. before his death.

During this time, Merton was also aware of a dangerous duplicity in discussions of race. He called out well-intentioned white people—and this is equally true today, Horan said—for supporting black rights, but only so far as it doesn’t affect their own preferred way of life. Combatting this phenomenon was a central focus of Merton’s activism, and the friar urged us to take his words his words to heart.

Horan then shifted his discussion to the third subject, reminding us that, for all of his insight and prophetic wisdom, Merton’s writings are not without flaws.

“Merton’s own white self-criticality was limited by his own socialization, which despite his best intentions nevertheless prevented him many times from recognizing his own whiteness as a marker of race itself,” Horan said.

In other words: Thomas Merton was still a man, subject to the same ingrained cultural biases that we all are. The difference?

“For all his contextual and self-critical limitations,” Horan said, “at least Thomas Merton was able to plainly state that in the United States, racism has been, and remains, a white problem.”

As I walked out at the end of the lecture, the weight of Horan’s words began to hit me. The full reality of American racism, in all its systemic, day-to-day enormity, can never be fully understood by anyone who lives his or her life in the majority. Conversely, the depth of white privilege is only truly discernible through the eyes of those who don’t have it.

Black History Month is over, but the struggle for social justice has no end in sight. Horan’s deeply relevant insight on this struggle is a personal and spiritual inspiration, but also a crucial reminder that our society’s greatest shortcomings are nothing new.