By: Logan D Clark

Due to the status of the prison inmates, their identities cannot be included in the story.

Although Dr. Carol Smith spends majority of her time teaching nursing classes at Bellarmine, her love for volleyball remains strong.

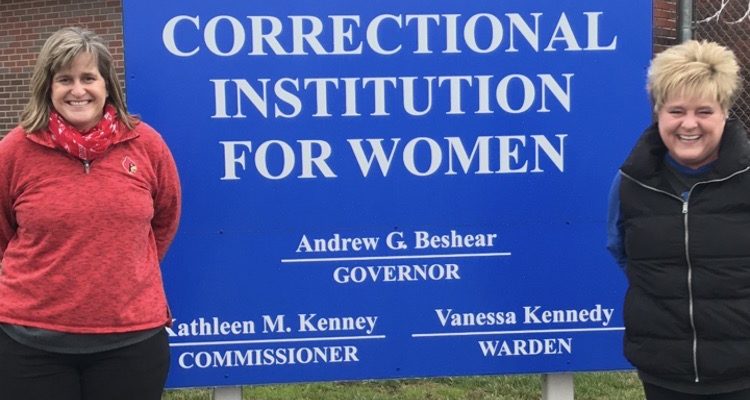

Smith is an associate professor of critical care in the Donna and Allan Lansing School of Nursing and Clinical Sciences and has been at Bellarmine since 2001. As a nurse practitioner, Smith also spends a lot of her time volunteering at free clinics.

She has been playing volleyball all her life, and belonging to St. Aloysius Catholic Church has only broadened her ability to play and now coach. Around 2002, female members from the church got together with members of other churches to form a team to play against a team from the Kentucky Correctional Institution for Women (KCIW).

St. Aloysius is down the street from KCIW in Shelby County.

In the beginning, the church team visited the prison two or three times a year and played four or five hours at a time. Smith said that three or four years after this started, the coaches for the prison team were dismissed because of budget cuts, and for the program to continue, Smith and her friend, Paula Haysley, volunteered to coach the inmates.

Haysley is a human resources representative for United Parcel Service (UPS) and has been there for over 30 years. She said that the time she has spent volunteering at the women’s prison has been fulfilling.

Smith said: “Paula and I now go to the prison every other Monday night. We have had some really good teams come through whether they be members from the church league or the prison. It’s very open, as long as you’re female.”

Getting into the prison isn’t as easy as you would think. You have to have a full background check. Smith and Haysley attend classes every year about what to do and not to do in certain situations. Once they are searched, they can walk straight in and to the gym. “It’s probably a five- to six-minute walk once you’re inside,” Smith said.

Smith said prior to the prison system overhaul in 2013, KCIW was a minimum- and maximum-security prison. After the rearrangement, KCIW became a maximum-security prison only.

“What that did for the team was no one was going anywhere; they’re there for a while,” Smith said.

The prisoners don’t know much about Smith other than that she is married, has children, and is a die-hard Louisville Cardinals fan.

“There is a running joke in my house,” Smith said. “When students or friends would call the house, my kids (when they were younger) would always say ‘Mom’s not here. She’s in prison.’ And they loved that. While the person on the other end of the phone didn’t understand, my kids sure knew what they were doing.”

One of the things the prisoners struggle with, Smith said, is the change in technology. “One of the inmates has been in there since the early ‘80s. She was up for parole recently, and someone came in to prep her and cell phones came up. She had no idea what a cell phone was, and that scared her. She had been institutionalized and had no idea how to react to things.”

Smith said before the change to maximum security, the prison was “like a revolving door.”

“Some weeks there would be four players, and other weeks there would be 20,” Smith said. “That helped as far as having a consistent team. However, the anger management and aggressiveness increased significantly, resulting in more violence.”

Although Smith has never felt threatened during her visits to the prison, she has had to de-escalate some anger management.

“Many of these women have mental issues and they have to deal with the fact that they’re in prison for the rest of their life,” she said. “Because of my nursing training, and Paula’s human resource skills, we’ve been trained to deal with situations like that.”

The prisoners know if something happens to Smith or Haysley, the program would be disbanded. Smith said the prisoners “jump” on one another quickly to de-escalate issues.

Smith said prison life is very segregated. “On the team they learn how to work together. But when tempers flare, the lines come back out again,” she said. “We’re trying to blur those lines, but it is a ‘survive’ atmosphere.”

Smith and Haysley make sure the prisoners know they are cared about. Inmantes said, “It makes them feel happy and loved knowing that someone is actually taking the time to pray and subsequently care about them.”

Smith said, “One of the biggest things we, as a team, preach on in the prison is learning to trust the person next to them. Our team is very good. I don’t think we could compete with the Bellarmine volleyball team, but I bet we could give them a run for their money.”

Haysley said that volunteering as a volleyball coach at the prison has been very rewarding. She said: “The women I have encountered over the past several years have definitely impacted my life tremendously. Through their respect for us as being coaches, they have shared many aspects of their personal lives and challenges they face while being incarcerated.

“We have witnessed many transformations in these ladies. They have become a team – united as one. We encourage them and let them know God is with them always.”

Smith said one of the things she enjoys most at the prison is participating in the Paws for Purpose program, where prisoners train dogs for people with disabilities. “Prisoners will often bring the dogs to the games to help them get used to loud noises and not reacting. It’s great because I’m surrounded by 20 puppies,” she said.

Smith said KCIW has rules she wasn’t aware of, including what to do if the power goes out. Smith has experienced this before and said it was “intense.”

“All the prisoners dropped to the floor and said that I needed to get down, too. I said I was not getting down anywhere,” Smith said.

“Once we were given the all clear, I told the prisoners to go ahead and run back to their bunks. One inmate said, ‘Well coach, if we run, we get shot at. So, we can’t do that.’”

Smith said the inmates tell the coaches often how much they appreciate the time that her and Haysley spend and volunteer with them. “They talk very often to us [Smith and Haylsey] about how comfortable they feel opening up about their personal struggles,” Smith said.

One inmate expressed missing her children and how she is struggling with potential parole meetings. Smith said, “Many of these women have been out of the ‘mainstream’ for so long it is overwhelming.”

Smith said she doesn’t see herself leaving her prison coaching position anytime soon. They take time to relax over the summer and have a mental break but continue to keep coaching each year.